“I am a person with dementia and a person with rights.” (Part two)

In part two of this series, we look at how the rights enshrined in the U.N.’s Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities can specifically apply to people living with dementia.

Part two: Understanding dementia from a human rights’ perspective

When we last left Phyllis Fehr, we heard about how her experiences inspired her to take on her current role as a leading advocate for human rights for people with dementia. (If you haven’t yet, check out part one of this series, Becoming a force for change—Phyllis Fehr’s story.)

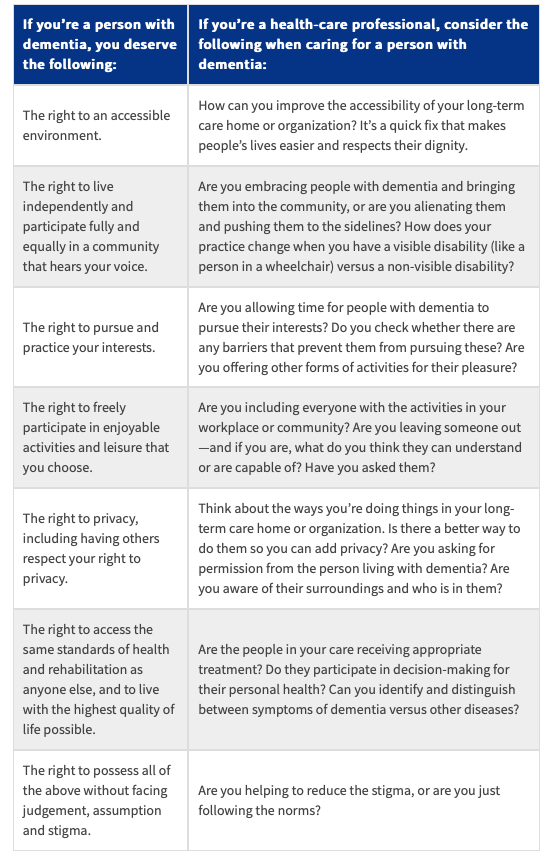

One of Phyllis’ current focuses is the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, an international human rights treaty that was adopted by the United Nations almost a decade ago. What makes the Convention an important document for people with dementia, as well as health-care professionals? Among the treaty’s 50 articles on human rights, Phyllis identifies seven that can help improve your day-to-day living.

“People with dementia are often not included in making society more accessible for them,” says Phyllis. “The purpose of the Convention is to promote, protect and ensure the full and equal enjoyment of all human rights and all fundamental freedoms by persons with disabilities and to promote respect for their inherent dignity.”

As a person with dementia, do you know your rights? As a health-care professional, how can you ensure that the rights of the person you’re caring for are properly addressed (if they’re even addressed at all)?

Based on her personal experiences, here are Phyllis’ seven recommendations that will help you improve your quality of life or learn to be more inclusive and respectful of people with dementia.

Article 9 – Accessibility

Remember Phyllis’ experience at a grocery store in part one? Unable to remember what she was there for, she found it difficult to get around. Had there been more visible signage in the store, perhaps Phyllis would have been able to get around easier. Phyllis’ experience is a familiar one for people with dementia—going out and about should be a normal event, but there is always a chance they may find themselves lost and confused in a public space.

Example of prominent washroom signage

Consider signage for a public bathroom. Instead of placing the sign on the door, place it above and sticking out where it can be seen clearly. Otherwise, a person looking for a bathroom may have to ask for help unnecessarily, fostering dependence rather than independence. As Phyllis points out, “If you’re a person with dementia, you’re not going to want to go out if you’re afraid to find bathrooms during your outing.”

Here’s another example. Accessible transit, such as HandyDART in Vancouver or WheelTrans in Toronto, is not always as accessible as its name would indicate. For one thing, the guidelines to qualify for accessible transit often include a requirement to only be able to walk a certain distance. This can leave many people with young onset dementia out in the cold—literally speaking! Though they’re fully mobile and able to get around, there’s still a danger of getting lost while walking the few blocks to catch the bus.

But even those who qualify for door-to-door accessible transit are not immune from other problems. Phyllis likes to give the example of a doctor’s appointment; if the appointment takes place in a hospital, accessible transit will drop the person off at the hospital doors, but the individual may still get lost on their way from the drop-off to the room, or not remember the wayfinding instructions they were given.

If you’re taking accessible transit, or if you know someone arriving via accessible transit, make sure someone is at the drop-off point to meet and help navigate to the final destination. An accessible environment allows a person with dementia to live as independently as possible and participate fully in all aspects of life.

Article 19 – Living independently and being included in the community

Speaking of living independently, Article 19 recognizes the right of a person with a disability to do so. At the same time, the person also has the right to have full and inclusive participation in their community with choice equal to their neighbours.

Phyllis remembers her grandparents, who attended church for years to the point that they had an unofficial spot in the pews. Her grandfather, who was in a wheelchair, would always receive help to get in and out of the pews. However, Phyllis’ grandmother, who had dementia, had her seat gradually taken by other people over time. Eventually, she was pushed to the side and finally to the back of the church, where she received no assistance.

Phyllis also thinks of her mother, who has dementia and is currently living in a nursing home. Whenever Phyllis visits, they go out, play bingo, or go bowling. However, her mother never participates in any activities at the nursing home.

“In the beginning, they included her in programs, but it didn’t take long before my mother was left sitting in her room, or in the common area in a chair, looking out the window,” said Phyllis. “How is that including her in the community?”

Phyllis’ grandmother and mother were denied their right to be an equal member of their community, with people assuming that they were incapable due to their dementia.

Article 21 – Freedom of expression and opinion, and access to information and Article 30 – Participation in cultural life, recreation, leisure and sport

These articles are about the right to personal enjoyment—hobbies, passions and skills. The ability to learn something new is often taken for granted. For a person with dementia, it can, unfortunately, be disregarded entirely.

Phyllis’ mother was not invited to bingo nights at her nursing home, even though she loved to play. One of her favourite pastimes was reading the newspaper, yet the nursing home staff never offered her a paper.

“They had already decided for her that because she had dementia, she didn’t need to read,” said Phyllis.

Thankfully, technology makes it easier for people like Phyllis’ mother to exercise their right to pursue their interests. With a tablet, her mother can play her favourite audiobook or the music that she likes. Furthermore, keeping the brain stimulated will help Phyllis’ mother to be active longer and allow her to be more involved in the community.

Article 22 – Respect for privacy

On the day that Phyllis was diagnosed, she was asked to bring a family member. Choosing her husband, the pair received the news at the same time. While Phyllis was prepared and accepting of the diagnosis, her husband was more distraught. Making matters worse, the doctor didn’t speak directly to Phyllis, but to her husband instead.

“While I accepted this at the time because ‘this is how it’s done,’ now I find this practice disturbing,” said Phyllis. “While understandable, you have to ask why your right to privacy is being taken away when you’re still capable of handling this on your own?”

Indeed, if you have dementia, you may be used to your privacy being compromised. In many long-term care homes, for instance, there are four residents per room, so every word spoken is heard. How can that fulfil a reasonable expectation of privacy?

Article 25 – Health and Article 26 – Habilitation and rehabilitation

While Phyllis’ diagnosis was the beginning of a new chapter in her life, it was also the endpoint of another—four years of referrals to seek the answer to her troubles. Though she made repeated appointments with her family doctor, Phyllis was never referred to a specialist.

As a person with dementia, you may have been told, prior to diagnosis, that the problems you were experiencing had to do with something else, perhaps some other problem to do with aging. Rather than receiving an early and accurate diagnosis, you were kept in the dark.

“You have the right to enjoy the highest attainable standard of health without discrimination on the basis of having dementia,” says Phyllis. “Involving the person with dementia is a more positive and tenable solution than pushing them away.”

Another problem that people with dementia face is the lack of immediate care.

When someone has a stroke, for example, “they’re automatically offered rehabilitation like physiotherapy, occupational therapy and speech and language therapy,” says Phyllis. “If someone receives a diagnosis of dementia, they receive nothing in the beginning, not until they have started to decline…if they even get an offer of therapy!”

And what happens if someone with dementia becomes nonverbal, or isn’t able to stand up? They may be experiencing a stroke. As a health-care professional, be careful that you are not misattributing these symptoms to dementia. Ironically, people with dementia are not offered the same level of rehabilitation if they suffer an attack like a stroke.

With their health needs unmet, people with dementia are unable to maintain physical, mental and social independence. Caregivers and health-care professionals must be able to tell the difference between symptoms and react appropriately.

“And if you’re proactive,” Phyllis adds, “you can avoid problems that people with dementia face, like loss of physical activity and socialization.”

Summary

Knowing and understanding human rights is essential for people with dementia. After all, they have meaning in each part of our lives—social, leisure, health and more. By recognizing and removing the barriers in our day-to-day experiences, people with dementia such as Phyllis and her mother can participate in society fully, openly and without discrimination.

Whether you are a person living with dementia or a health care provider, following these seven articles is an excellent start to understanding dementia with the help of human rights.

This is the second piece in a blog series based on the webinar, “I am a person with dementia and a person with rights,” hosted by brainXchange and presented by Phyllis Fehr in December 2017 and January 2018.

In Part three: Establishing human rights for Canadians with dementia, we conclude this series by looking at a prospective charter that will protect and respect the rights of people with dementia.